I’m a big sci-fi nerd. I love a good story, but I particularly love a good sci-fi story. What I’ve seen about any good story is that is says something fundamentally important about humanity. About being human.

We see this question frequently in good sci-fi. What would the first Star Trek series be without the question of Spock’s humanity? (Spoiler alert!) His death in The Wrath of Khan (1982) serves as the climax to this question. “I have been and always will be your friend” the uber-logical Spock says to his impulsively uber-human friend, Captain Kirk.

We have plenty of other examples of this. Commander Data’s quest to be human is central to his role in Star Trek: The Next Generation. Darth Vader serves this capacity at the end of Episode VI: his humanity is demonstrated in his final rejection of Darth Sidious and his embrace of fatherhood. For Vader, “The power of the Dark Side” is overcome when he embraces something more powerful, and Vader sacrifices himself to save his son.

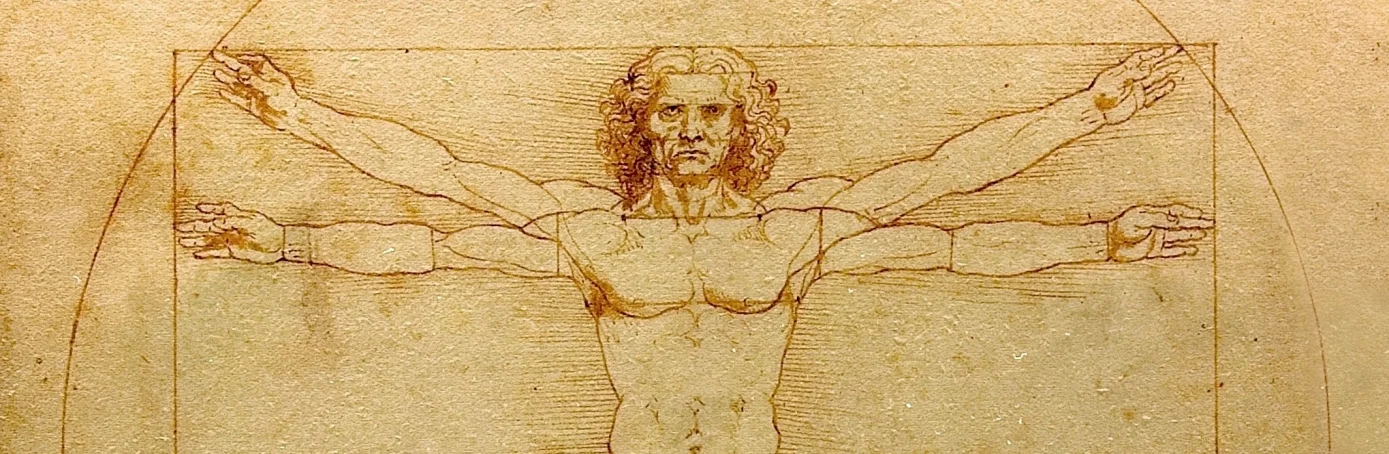

What does it mean to be human? This important question is central for a vast portion of good literature. What does it mean to be human in the context of a story taking place in the English Navy of 1800? Or in the context of a fantastic future world? The characters we most identify with are those characters who show us something about ourselves.

Getting the Story Right from the Start

I sometimes take part in conversations where one of the Christian conversation partners makes an off-handed comment: “that’s human nature!” And of course, it’s understood that by “human nature” they mean the evil inclination of our heart. But it this right? Should we call human nature to account when we discuss issues like sin and sinfulness?

The Bible itself has something important to say about “being human”. We learn from the Bible that our basic nature is actually “very good”. God creates everything with a word. Then God steps down and molds human beings with His very hands. And from the very start, God calls it all “very good” (Gen. 1:31). So whatever we have to say about the most basic nature of humanity, God calls it, along with everything else He made, “very good”. Whatever else it means to be human? It does not mean “evil inclination” or “sinfulness”. Those are intruders in the story.

And doesn’t this touch on the Christmas story itself? When we talk about Christmas, we’re talking about the second Member of the Trinity becoming flesh and dwelling among us. When we talk about the Christmas story, we’re talking about God being “with us” in the very real sense that God has become one among us. Whatever else Jesus was, Jesus was a very human being.

Jesus Christ: More Human than Human

It’s been my observation that, in our circles at least, when we discuss the person of Jesus Christ we tend toward understanding Him as the Divine One, the fullness of God. He is the one whom we worship on Sundays. He is the one in whose name we pray. It’s rather easy for us to see Him as “fully God”. It’s also rather easy for us to forget that He is “fully human”.

It’s easy in our circles to remember Jesus, the second Member of the Trinity. And we have a hard time seeing him as the second Adam. We have a hard time identifying with Him because, well, Jesus was and is God-in-flesh. God, yes. But weak? Frail? “With us” in the sense that this Person is, really and truly, a human being with human emotions and human desires? Did Jesus laugh with his friends? Did He think hummus tasted better than lamb? Did he think girls were pretty? Did He ever hit his thumb with a hammer? And did he jump up and down in pain, if he ever made such a human gaffe? We have a hard time entertaining such questions because we dare not touch his humanity for the sake of His Divinity.

But here is precisely where the story informs us about ourselves. We can and should identify with Jesus in His humanity because He is what humanity was meant to be. Jesus exemplifies for us what Adam should have been. What does it mean to be human? We need look no further than a general contract worker living on the edges of Empire and the fringes of Ethnic Identity. Whatever we ought to be is provided for us in the the story of a very real human being, in a man who calls us to that same humanity.

In looking for our true humanity, we have become the “Spocks,” looking in on the real human. We have become the “Commander Datas",” wanting to touch, taste, and smell humanity as Jesus tasted it for us. We have become the Darth Vaders, seeing that the power of our dark hearts, enslaved as we once were to our darkness, is weak and lifeless compared with the life we find in the true King, whose slave we have gladly become.

Sin is an intruder on this human story. But sinfulness is not what it means to be truly human. Not because Jesus is God (which is true) but because Jesus was born of a woman, born of a promise. His sinlessness doesn’t make Jesus less human. His sinlessness makes him more human. And He calls us out of our own sin toward this true humanity by the power of the Holy Spirit. Jesus frees us from our sinfulness, not from our humanity.

So Merry Christmas, everyone! The Incarnate God was born in flesh 2,000 years ago. And most amazingly, this Incarnate God—Immanuel—has taught us our humanity best.